"A True Photograph need not be explained, nor can it be contained in words" - Ansel Adams

While this holds true in the visual appreciation of a photo, when purchasing at auction you may want to be a little more loquacious. At a lecture in conjunction with Heritage’s October photography auction in New York City, OTE staff picked up some tips for collecting photographs. Rachel Peart, Heritage Director of Photography and Alice Sachs, the President of Art + Business Partners and an avid collector of photography, stressed a number of elements important for buyers to evaluate, whether purchasing from an auction or private sale.

The market for photography has remained relative stable over the last couple of years and as of June of this year ArtTactic reported the overall confidence in the market increased by 9 percent. Sales at auction have also increased. The Modern Photography market saw a 22 percent increase and the Vintage photography market had a particularly large increase of 125 percent, while the market for Contemporary photography remained the same from 2012 to 2013 (ArtTactic Photography Market Report January 2014). However, it is the Contemporary market that continues to drive sales at the top end. Prices for iconic photographers (i.e. Man Ray and Alfred Stieglitz) can get into the hundreds of thousands of dollars while a large percentage of sales are affordable, under $10,000.

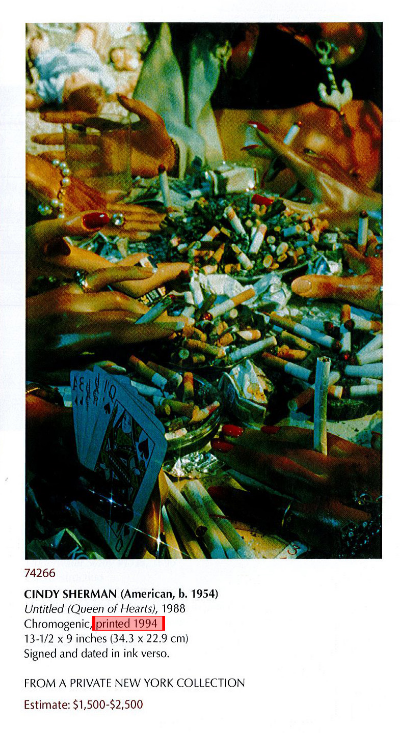

The photography market is a tricky one. Collecting is often motivated by rarity and personal aesthetics, which makes paying attention to a photograph’s catalog description key. This may seem basic, but interpreting how a photograph’s print date and the print type relate to an artist’s market is more confusing than it looks. In a typical description of a photographic lot at auction there is the artist’s name followed by the italicized title and a date (in red in the example). This represents the 'negative date' – the date when the photographer took the image.

The actual date when the photography was printed is usually found either next to or as a part of the type of print (gold star above). For the Bernice Abbott photograph above “Vintage” is the only indication of when the photograph was printed. Some photographs, like the Cindy Sherman photograph on the right, are accompanied by the exact printing date (also in red). The print date informs a collector about how the specific photograph fits into the timeline of an artist’s body of work. The context of a photograph produced significantly later than the negative date is different than one printed close to when the photograph was originally taken and is a variable to be taken into account when purchasing.

Here is a guide to non-specific print date references:

- Vintage Print: printed within five years of the negative.

- Early Print: printed within ten years of the negative.

- Later Print: printed at least ten years after the negative.

- Modern Print- printed many years after the negative.

- Posthumous Print: printed after the death of the artist.

- Contemporary Print: currently being printed.

How much the date of printing matters in the valuation of a photograph depends on the artist. Bill Brandt’s (British, 1904-1983) later prints are darker and are valued differently than his early prints. Some descriptions will specify the person who printed them. If someone other than the artist printed the photograph it can have a strong impact on value; positive or negative, depending on their relationship with the artist. Photographs by Ed Weston (American, 1886-1958) printed by his sons are considered valuable because they were trained by him and followed his methods, but if the photographs were printed by another party this would likely not be the case. The type of photograph (the process used to create the print) is a variable that should not be overlooked.

The most common types of photographs seen at auction are:

- Gelatin Silver: a black and white print made from 1870s to the 20th century.

- Chromogenic prints: (also referred to as C-prints) color prints made since 1940.

- Dye Transfer: color prints made since 1928.

- Digital prints: (also called Digital Inkjet prints) a printing process developed recently.

In looking at the type of print it is helpful to know an artist’s typical practice. While rarity is often a positive attribute, this is not true in all instances. Ansel Adams is well known for his gelatin silver photographs in black and white and though his color photographs are rarer they are not as well received at auction. Aesthetic considerations aside, successful purchasing decisions are often based on understanding what specifically to pay attention to for an individual artist.

This blog referenced information from:

- Ansel Adams, Glossary of Photographic Terms, http://www.anseladams.com/ansel-adams-photography/original-photographs-by-ansel-adams/glossary-of-photographic-terms/

- ArtTactic, The Market for Photography, http://www.arttactic.com/art-markets-home-pages/photography-art-market.html

- Definitions of Print Processes, http://www.photoeye.com/Gallery/Definitions.cfm

- Catalogue Examples from Heritage’s October 16, 2014 Photographs Auction